For more than a decade, the U.S. stock market has been the place to be for global equity investors. But as we continue to emerge from the inflationary induced bear market over the last two years, developed international and emerging markets may be worth a closer look.

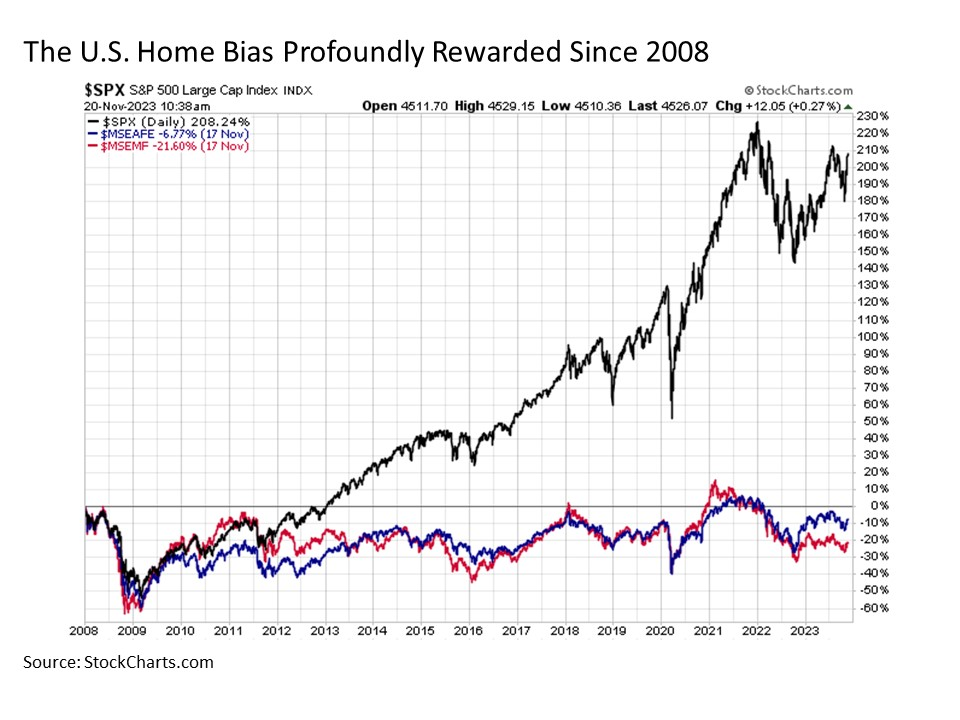

Long time gone. U.S. stocks have enjoyed a global stock market dynasty since the start of the last decade. While the U.S. benchmark S&P 500 Index moved in lockstep with the developed international’s MSCI EAFE Index and the emerging market bogey MSCI Emerging Market Free Index from the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 through its immediate aftermath in early 2010, U.S. stocks subsequently diverged and took off into the skies, leaving its developed international and emerging market counterparts stuck on the ground.

In the time since, the relative performance has been striking. While the S&P 500 Index has cumulatively risen by over 200% on a price basis alone since the start of 2008 through today, both the MSCI EAFE and MSCI Emerging Market Free indices have cumulatively fallen on a price basis by -8% and -21%, respectively, over this same time period. Put simply, outside of brief pockets of relative performance along the way, U.S. home bias has been resoundingly rewarded for domestic investors for as long as many investors can even remember.

Time to fly. Before going any further, it’s important to emphasize that asset allocation is not a binary choice. Just like a traveler deciding to spend more time in Europe doesn’t mean that they have decided to sell their home and move their belongings to a new continent, an investor considering an increased non-U.S. equity exposure is likely doing so on the margins in the context of their already established asset allocation strategy. More specifically, for an investor that may have had a prolonged minimal to zero weighting to developed international and emerging markets in the equity category of their asset allocation models, any such increase in weightings may result in taking on positions that still represent a relative underweight. But even if it is a smaller underweight, such a shift can still have a measurable impact on portfolio returns.

So why then should investors consider placing a greater emphasis on developed international and emerging market equities today? The following are a few key reasons.

The world has evolved. First, the fundamental and policy environment that had supported U.S. stocks over developed international and emerging markets for so many years has changed. In the wake of the financial crisis, the global economy was mired in a rut of chronically sluggish growth and the threat of disinflation if not outright deflation. This caused monetary policy makers from around the world to engage in continuously easy monetary policy marked by zero if not negative interest rates and successive rounds of asset purchase programs such as quantitative easing. In short, the global financial system was awash in liquidity but with limited prospects of robust sustained growth for this capital to find a destination. Understandably, global equity investors migrated to where their capital would be safest and treated best, which was the U.S. market in the select few names, many of which were found in the technology or technology adjacent sectors (consumer discretionary, communications services), where outsize growth and free cash flow was being generated. This concentrated migration of capital continued for years regardless of the valuations of the underlying stock names.

But in the wake of COVID and the excessive policy response that resulted in our worst outbreak of inflation since the hyperinflationary 1970s, underlying fundamental conditions have dramatically changed. Instead of chronically sluggish economic growth and stubbornly low inflation, we have bigger swings in economic activity and an inflation rate that while still coming down appears set to settle in measurably above the 2% target rate that proved elusive for so many years. Why? The increasing shift toward deglobalization and the potential for ongoing supply chain disruptions are just a few of the reasons. The positive result is that global central banks were finally able to break the zero bound policy spell. This includes the U.S. Federal Reserve, which has been able to raise the Target Fed Funds rate above 5% and keep it there without breaking too much along the way save a few systemically important financial institutions (SIFI) along the way to date. And the opportunities that investors are likely to pursue going forward in an environment of more uneven economic growth, relatively higher inflation, and historically more normal policy rates are likely to be considerably different than before. This includes a greater sensitivity to valuation versus what we have seen in the past.

Great travel deals abound. It is important to note that the U.S. economic outlook is stronger going forward relative to many of its global peers. For example, the growth outlook across Europe is far more challenged than the U.S. heading into 2024. But just as a good company does not necessarily make the best stock to own right now, a relatively stronger economy does not necessarily make the best market to allocate all of your capital right now. A key question that is worth asking in this regard is the following: at what price?

A key fundamental factor confronting U.S. stock investors emerging from the recent bear market is valuation. While down from the 22x to 24x multiples from a few years ago, U.S. stocks are still trading at nearly 19x forward earnings today. This still marks some of the highest forward P/E multiples we have seen in U.S. stocks in history and has the risk of creating a mounting headwind for further gains in U.S. stocks, particularly in an environment where the Fed funds rate may stay “higher for longer” in the 5% range (negative equity risk premium means TINA “there is no alternative” has become TARA “there are reasonable alternatives”).

But this valuation hurdle does not exist in most parts of the world outside of the U.S. Instead, many developed and emerging markets are trading at their most deeply discounted valuations in decades. This includes absolute multiples in many cases that have fallen toward if not well into the single-digits. As just a few examples, the United Kingdom is now trading at 10x forward earnings, which is its cheapest multiple since at least the early 1990s, Greece is trading at 9x that marks its lowest multiple since the “PIIGS” era of the early 2010s, and Turkey is trading at less than 5x forward earnings that speaks for itself. All of these economies have deep challenges and growth obstacles to varying degrees. But at such deeply discounted absolute and relative valuations, many foreign markets like these represent outsize total return opportunities going forward for those investors that have the specialized knowledge and expertise to navigate these markets. In other words, markets. In other words, just like a value investor in the U.S., you need to know where you are going and what you are doing (or have someone who knows what they are doing) when considering allocating to some of these deeply discounted non-U.S. markets.

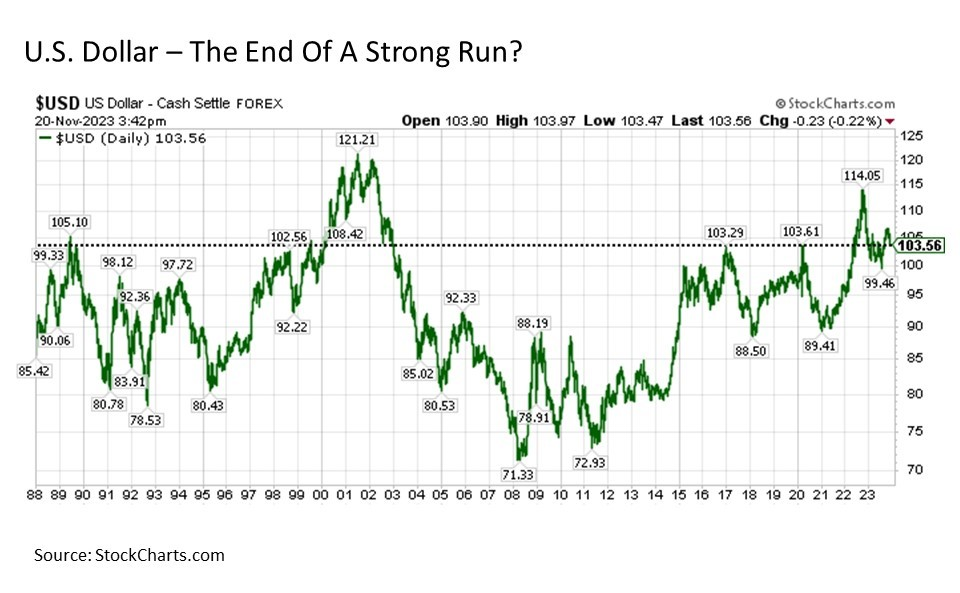

Foreign exchange. An added tailwind supporting the case for traveling abroad in an investment portfolio comes from the foreign exchange side of the equation. The U.S. dollar is still coming off of its highest exchange rates relative to leading global foreign currencies. The latest sharp U.S. dollar run up was driven by the outbreak of high inflation in the U.S. and the realization that the U.S. Federal Reserve needed to hike interest rates sharply and aggressively in order to combat and defeat flaming pricing pressures, as tightening monetary policy and sharply rising interest rates will strengthen your currency relative to the rest of the world.

But where we increasingly stand today is that the U.S. Federal Reserve is almost certainly finished raising interest rates with inflationary pressures continuing to come back down. Instead, the conversation that this Chief Market Strategist considers highly premature but is taking place nonetheless is around the Fed cutting rates as soon as early to mid-2024. This stands in sharp contrast to many other economies and central banks around the world, however, as many countries are still actively engaged in a monetary policy fight to bring inflationary pressures under control.

A potentially easier U.S. monetary policy coupled with a still tightening monetary policy in many other parts of the world suggest the potential for a sustainably weaker U.S. dollar going forward. And this would create a meaningful tailwind for developed international and emerging stocks that derive a measurable percentage of their total return from currency exchange rate effects.

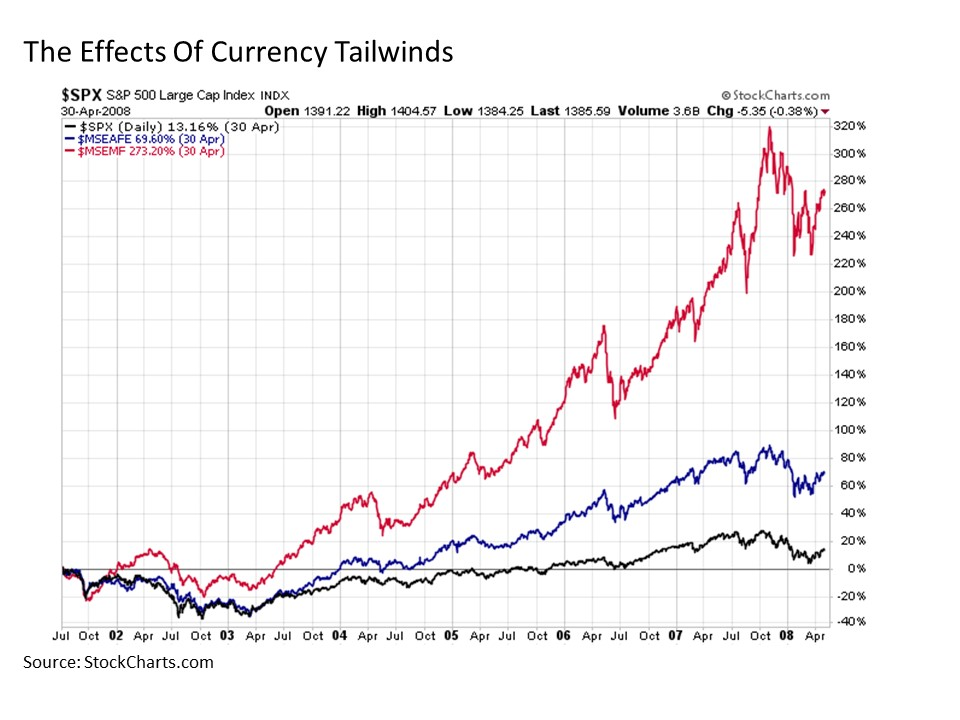

To highlight the relative return effects on developed international and emerging markets from a sustainably weakening U.S. dollar, consider the period from mid-2001 through early 2008 as shown in the earlier U.S. dollar chart above. During this time period, the U.S. stock market was the chronic laggard generating a cumulative price return of just over +10%. At the same time, developed international stocks were cumulatively higher on a price only basis by nearly +70%, while higher beta emerging market stocks advanced by more than +270% on the same measure.

Setting your travel itinerary. A final point is worth emphasizing when it comes to allocating to developed international and emerging equity markets. The conventional approach for many investors is to simply allocate to these non-U.S. markets through a passive index approach where markets are weighted based on their size. It should be noted, however, that this may not be the most effective way to capture the total return potential from non-U.S. markets. For example, just because a country’s stock market happens to be relatively large based in large part on the size of its underlying economy, this does not mean that it is necessarily a good destination for equity allocations at a similar proportion to its market size. More specifically, just because China is the second largest economy in the world that makes up roughly 30% of the MSCI Emerging Market Free Index doesn’t mean that my best choice from a capital allocation standpoint is to send 30 cents out of every dollar of my emerging market equity allocation to China. Closer research may reveal that other markets that may be relatively much smaller (or not included in the benchmark indices entirely) may offer far better and sustainable total return opportunities that justify a meaningful overweight at the expense of an underweight to a relatively massive market like China. This is where identifying expert managers with proven track records has the potential to add measurable value when operating in these more specialized segments of capital markets.

Bottom line. While the U.S. remains an ideal location to overweight equity capital allocations relative to the rest of the world, we have potentially arrived at a juncture where having developed international and emerging markets play an increasing role within a broader asset allocation framework may be warranted going forward.

Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article. Investment advice offered through Great Valley Advisor Group (GVA), a Registered Investment Advisor. I am solely an investment advisor representative of Great Valley Advisor Group, and not affiliated with LPL Financial. Any opinions or views expressed by me are not those of LPL Financial. This is not intended to be used as tax or legal advice. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly. Please consult a tax or legal professional for specific information and advice.

Compliance Tracking – #507965-1